Let’s face it – in today’s world, it’s nearly impossible to live even a modest life without taking on debt from time to time. Unfortunately, modest debt has given way to overwhelming debt for many – and the impact, given the fragility of our economy in this Covid existence – is frightening.

Now it’s easy to blame the borrower – and for sure – some of us have an irrational attraction to shiny, new things that we could live without in reasonable comfort. But on the other end of the consumer’s appetite, are lenders who seem to have abandoned conservative, risk-based banking practices, and instead seem willing to lend almost limitlessly so we can scratch our consumption itch.

The problem is that their ‘generosity’ has driven us to a point of financial morbidity. Translation: We’re sick – because we’re O/D-ing on debt.

The ‘throttling’ mechanism that used to keep both the banks and us out of trouble was the debt-to-income ratio – a key underwriting measure used by banks to assess our likelihood of repayment. In the 1970’s, bankers figured we were a good credit risk if all our monthly debt payments totaled 25% or less of our income. So if we made $4,000 a month ($48,000 a year), they’d cut us off from more credit when our total payments got to $1,000 a month.

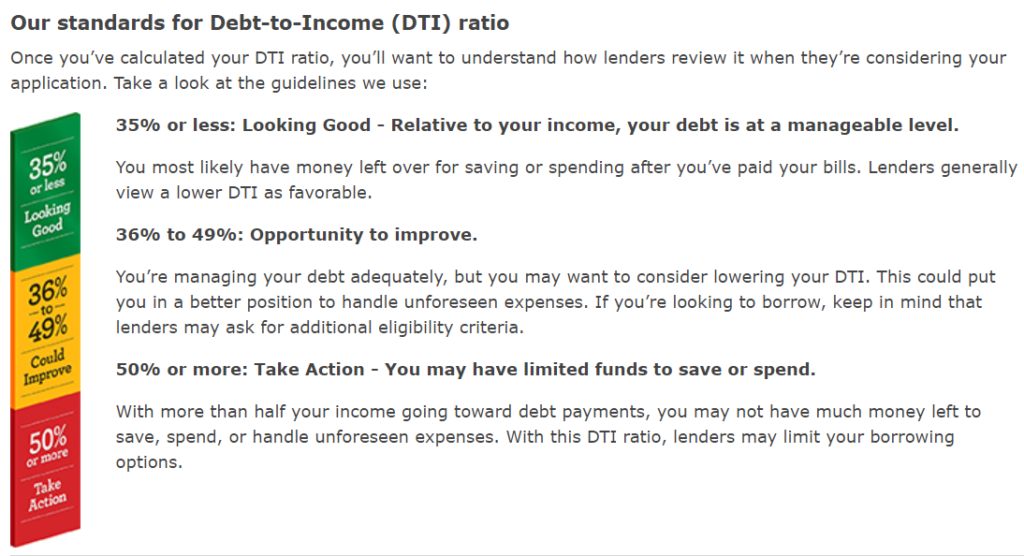

Trouble is – the banker’s appetite to lend and collect interest, has nearly matched our appetite to consume. Today, this is how they characterize what is to them – and acceptable debt-to-income ratio.

According to Wells Fargo – the fourth largest bank in America – only when debt payment exceeds 50% of income do they caution that “you may not have much money left to save, spend or handle unforeseen expenses…[and] lenders may limit your borrowing options?”

Wait a minute – a 25% DTI ratio in the 1970’s was an ‘acceptable’ bank risk – but today we can send them half our paycheck (actually more – because it’s 50% of GROSS income), before the banker starts to become concerned about our ability to manage the rest of our financial life?

It’s insanity. And it’s not only unhealthy for us as borrowers – it’s unhealthy for the banking system.

Recently, I was working with a college graduate now in his early 30’s. He still had over $80,000 of student debt. How? Because he had elected one of the government’s ‘income-based’ repayment plans. The good news (to him anyway) was that his payment was incredibly low and easy for him to make. But because his payment was so low (capped at a ‘reasonable’ percentage of his income), is wasn’t even enough to even pay the interest on his debt.

So while he reasoned that he was (slowly) chipping away at that $80,000 figure every month he made a payment, the reality was that because the payment wasn’t covering even the interest portion of the debt, his balance was actually getting larger each month. He was making payments – but owing more as a result.

To make matters worse, he wanted to buy a house and was looking at our company to help him pay off some debts on an accelerated basis to improve his credit score and create ‘room’ in his budget for the new mortgage payment.

To make progress, I told him we had to get those student loans going in the right direction. The least painful positive amortizing option was to go on a 20-year repayment plan – far from desirable (10 years would have been much better), but at least he’d be reducing the principal each month. Problem was, his payment would go up $500 a month on the 20-year plan.

I went on to suggest that I didn’t think there was any way he’d get a mortgage while those loans were negative amortizing. Then he shocked me. Apparently, the mortgage company had already pre-approved him. Because he has substantiated that the income-based payments were acceptable to the student loan lender, they would ignore the fact that they were negative amortizing.

This young man wasn’t stupid – he was a college graduate. But he was relying on the bank to tell him where the healthy limit was. The bank didn’t – wouldn’t. They were so interested in placing a new mortgage loan, they overlooked an insanely bloated DTI ratio and were ready to make him a homeowner – whether it was good for him or not.

My bet is that this guy will either declare bankruptcy at worst – or wake up at 45 with little or nothing saved for the future.

It would be easy to blame him – but to do so would be to convict him of naivety and inexperience. The banking industry can’t claim naivety – making them guilty of negligent and reckless lending.

We can’t count on institutions to help us understand what’s reasonable or not. The profit motive is too powerful. So we have to become more diligent – less naïve – ourselves. Make sure debt has an appropriate role in your life – not an unhealthy one. And if you want to explore ways to get debt paid off – fast – look us up sometime.